Why is moss important to humans? Read to the end and learn the environmental, Indigenous, and traditional medicine uses of mosses.

It’s our life’s work at Nectar Yoga Retreat to care for and deeply know this land, its forests, and waterways. This has always formed the core of our Bowen Island overnight stays, wellness retreat experiences, and meditation programs, intending to facilitate a slow-down that seeds consciousness, inspired by the immersion in the natural world. This year, Nectar’s blog spotlights some of our most beloved plant and funghi allies that can be found on Nexwlélexwm (Bowen Island). These green inhabitants are integral in shaping our natural world, and who, in many ways, make it possible for each of us—Bowen locals and visitors—to experience renewal and connection.

For the month of January, we’re finding ourselves enchanted by mosses, found just about everywhere on Bowen and the Pacific Northwest, and yet so often overlooked in the natural world. Stay with us to the end, and learn the types of plants mosses are, their ecological roles, identify 5 mosses commonly found in the Pacific Northwest, Indigenous and traditional uses of mosses, and a moss-inspired guided meditation.

What are Mosses?

Mosses are small, non-vascular plants that belong to the division of Bryophyta, that are fairly simple in structure. Unlike trees and many other plants, mosses lack the grandeur of true roots, flowers, or fruit. The leaves they do have are mostly only one-cell thick, and instead of seeding to reproduce, they spore or self-clone. Instead of roots, mosses produce rhizoids, tiny structures that anchor them to the earth and other surfaces, such as tree bark or rock, and help them absorb water and nutrients. Mosses thrive in damp, shaded environments, embracing their role as plush coverings of the forest.

Their diminutive size belies their resilience, tenacity, and ecological significance. Mosses have been on Earth for 400 million years, and appear to have endured through drastic changes and natural catastrophes. Mosses are essential for retaining soil and moisture (as much as 40 times their weight), preventing erosion, and providing homes, insulation, and sustenance for various organisms in their ecosystems, including at Nectar Yoga Retreat on Bowen Island.

Environmental Roles of Mosses

One of the better-known ecological roles of moss is as bioindicators of air pollution, such as those caused by carbon emissions. Because of mosses’ absorptive surfaces and reliance on atmospheric sources of water and nutrients, they are susceptible to most forms of air pollution, which can give scientists some necessary information in studies.

Mosses reduce soil erosion on recently disturbed areas. Some species, such as Funaria hygrometrica, can resist and regrow on burned soil. Many have an astonishing ability to endure moisture loss of up to 98% and bounce back to life once water is reintroduced.

In higher humidity settings, like on Bowen Island, numerous moss species host cyanobacteria. These cyanobacteria play a crucial role in transforming atmospheric nitrogen into a usable form for other plants, supplying vital nutrients to ecosystems with nitrogen limitations.

Mosses on rooftops and other hard surfaces in urban and suburban environments act as organic sponges that provide hydrobuffering, that is, reducing peak streamflows after storms and preventing wood shingles from overexpanding, when wet, then overshrinking, when dry. Because moss do not possess true roots, they do not pry apart shingles (contrary to a common misconception).

Moss is a plant, not a fungus. Pictured here, an image of moss growng on a winding tree branch.

Five Common Moss Varieties in the Pacific Northwest

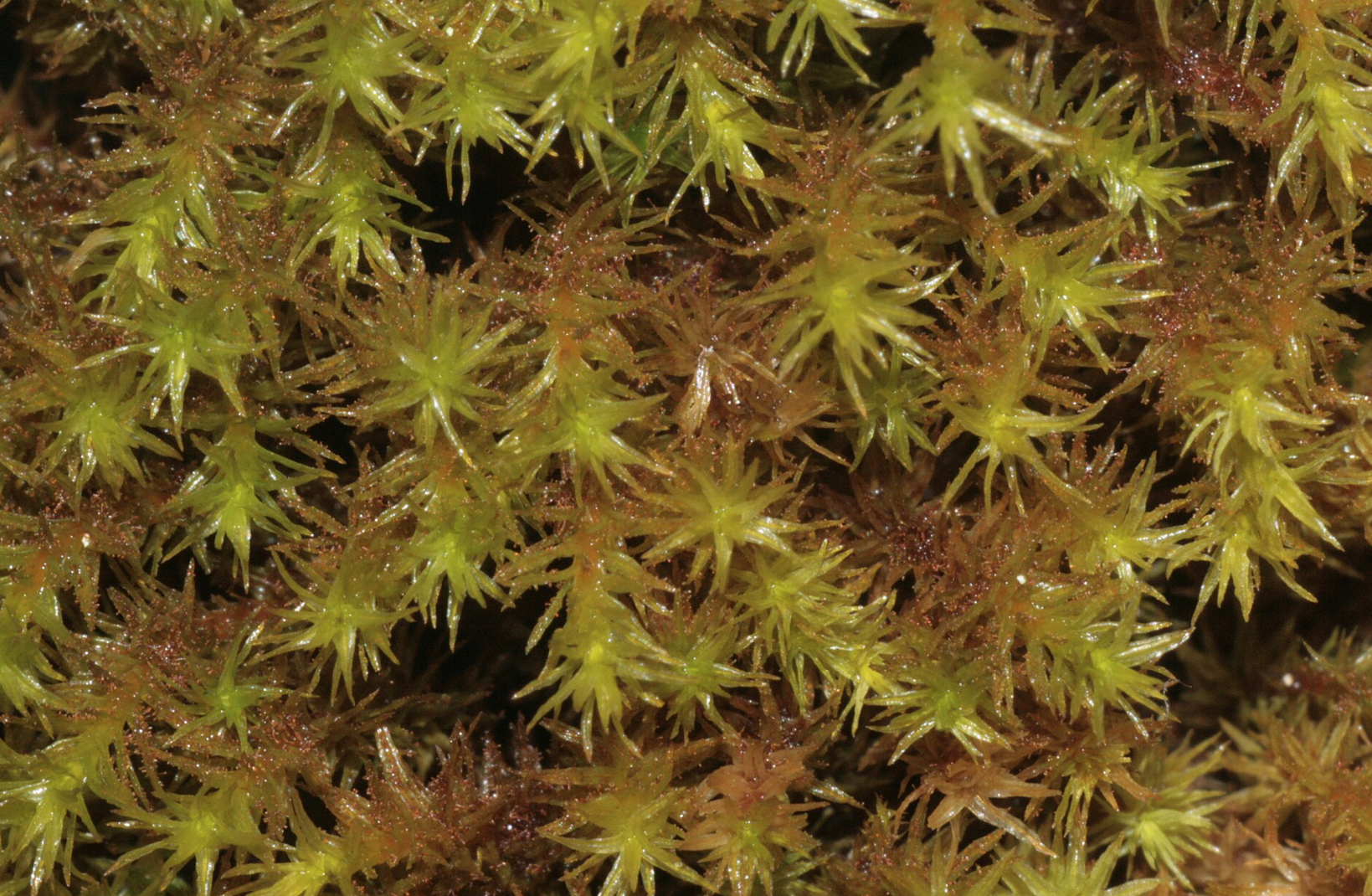

With a staggering count of ~22,000 species, experts say a significant portion remains obscure to the general public, with only a handful having received common names. Mosses thrive in areas where other plants cannot establish a foothold. Here are five common moss varieties that can be found on Bowen Island:

Sphagnum Moss (Sphagnum sericeum):

Sphagnum moss plays a central role in the formation of wetlands, nurturing a variety of flora and fauna. Their remarkable water-holding abilities allow them to grow in drier conditions compared to some other mosses.Oregon Beaked Moss (Kindbergia oregana):

Resembling tiny ferns, this bright, paler green moss is found in cooler areas in damp Pacific Northwest forests. Oregon Beaked Moss forms dense, vibrant mats on rocks, logs, and the forest floor.Curly Thatch Moss (Dicranoweisia cirrata):

Curly Thatch Moss grows in the form of relatively rounded tufts or pillows, and can be found on living and decomposing wood, tree trunks, and rocks.Sheet Moss or Bridal Veil Moss (Hypnum curvifolium):

With thick, plush growth that are shaped as tiny cypress leaves, Sheet Moss is also commonly called carpet moss, growing in damp forests, on the usual moss-loving surfaces.Big Toothed Umbrella Moss (Orthotrichum lyellii):

This moss adorns the bark of trees and rocks, concentrating in coastal temperate rainforests, near sea level elevations, such as on Bowen Island. They have a preference for growing on deciduous trees such as alders, maples, and oaks.

Indigenous and Traditional Uses of Mosses

In Gathering Moss, Robin Wall Kimmerer, a professor of environmental biology and the director of the Centre for Native Peoples and the Environment at the State University of New York, traces the eclipsed history of these ancient plants. She shares that traditional Northern people have lined their boots and mittens with plush mosses for insulation. Pillows made of Hypnum moss (Sheet Moss) were said to induce special dreams, making this moss a spiritual ally. Fishermen once used moss to clean freshly caught salmon. Kimmerer also notes that mosses were often used as diapers and towels.

On native-languages.org, traditional uses with First Nations groups for moss include stuffing for mattresses, lining cradles and bags. Some mosses, like Spanish moss and club moss, were also used as medicine herbs.

In a Scientist in Residence program, developed for Britannia Elementary School, Vancouver School District, notes that mosses were used to dress wounds - not only for their absorptivity, but also to impart antimicrobial properties naturally found in mosses such as Sphagnum. In an article Bryophytes Used in Folk Medicine: An Ethnobotanical Overview, Sphagnum has also been used for insect bites, acne, scabies, hemorrhoids, and to treat eye diseases.

One-of-a-kind Moss art by Bowen Island artist, Anne Marie Lewis, carried by Nectar Goods boutique. Image credit: Robin Bonner Photos.

A Year of Green Allies

As we live on Bowen and spend time with mosses and other plant and funghi friends, we are reminded just how essential it is to appreciate these, well, essential beings. Each time we walk the trails here on Nectar grounds, we see and feel the presence of these unassuming, yet wholly generous, beings. We love mosses so much that we also carry some beautiful moss works at our on-site boutique and e-shop, Nectar Goods, by a local Bowen Island artist Anne-Marie Lewis, as well as our house-brand candles that contain Oak Moss (a lichen technically, but the scent is so enthralling that we couldn’t resist).

We’re also inspired by other artists: Michael Woodcock and Ezra Woods of @pretendplantsandflowers lay down sheets of moss (what looks like Hypnum curvifolium) on tables for LA events. Brooklyn floral artist @joshuawerber creates miniature landscapes featuring moss and other enchanting greens, and Polly Nicholson of @bayntunflowers from the UK is inspired by kokedama, or Japanese moss balls, a century old art practice that is connected to bonsai cultivation.

Next time you find yourself wandering through a Pacific Northwest's verdant forests, perhaps you will also take a moment to notice their quiet presence.

Moss can be found all over Nectar Retreat grounds. Interesting facts about moss are covered here in this article. Image source: Pexels

A Moss Meditation

We like to close this article with perhaps an opening of sorts: A Guided Moss Meditation that can facilitate a reconnection to yourself and to these forest companions here on Bowen Island or anywhere you may find mosses. Be sure to check back on our blog next month, or better yet, sign up for our newsletters, as we continue to journey through the year with plants and funghi, and share wisdom and events on yoga, movement, meditation, and other wellness retreats and spiritual practices. For now, this January, to the mosses we go.

Find a day when the temperature is inviting, and your bare feet can embrace the earth. Venture into the forest, perhaps exploring one of Nectar Yoga Retreat's trails, or another trail on Bowen Island.

As you tiptoe beneath the lush tree canopy, let your senses come alive. Gradually, allow the entire soles of your feet to meet a patch of the moss-adorned forest floor. Gently and unhurried, place each foot on the ground.

Feel the soft tickle of moss against your heels, foot arches, and toes. Observe as it yields slowly to the weight of your presence. Lift each foot from the ground with the same unhurried pace.

Turn to look back. Have your footprints left an impression? How long does it take for the moss to regain its original density?

Dewdrops may tenderly caress your feet, offering a cool, refreshing sensation. Let not the chill deter you from taking one step, then another.

Now, settle down near or on a patch of vibrant moss.

Listen to the moss's silent wisdom.

Observe its intricate hues.

Feel the gentle texture beneath your fingers.

With a gentle hand, run your palm slowly across the moss.

To close, offering gratitude to this ancient, resilient life form that carpets the forest floor, rocks, and other surfaces.

Works Cited